Good-looking Bad Maps

Why do a lot of otherwise really good graphic designers design ineffective maps?

December 12, 2018

I took a tour of the new wing of a museum – building by a famous architect and wayfinding by an EGD firm. The signage was neat and beautifully detailed, if a bit understated. But with a modern glass and steel addition grafted onto the old nineteenth century structure, over-all museum orientation was challenging—the need for a good map directory was clear. We found a nice looking graphically-designed map in an appropriate location, but when I tried to orient myself I found that the north-up map was at right angles relative to my location and horizontal sightline—up on the map was actually to my right; what was to my left in real space was on down on the map, etc. This requires the user to mentally flip the map, making it unusable for many visitors. When I quizzed our facility manager guide, he said that’s the way the designer wanted it and after all, it was by an expert firm.

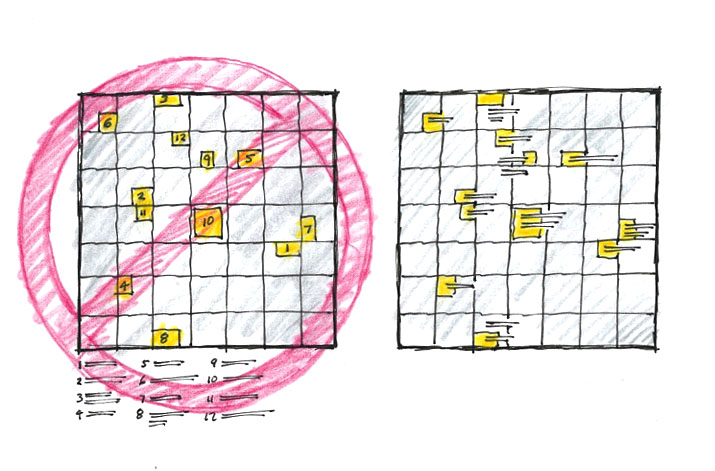

I encountered a very clean map on a well-known waterfront, again, graphically-designed—bold and simple lines for the streets, abstracted blue form for the water and neat squares for the destinations. But, the eight or nine destination squares had only numbers, not place names—I had to find and visually scan a list-form legend and then match the numbers on the map to identify the area’s places. Unnecessary mental gymnastics. Comparing locational relationships was also very difficult—I wanted to get to the aquarium and I was near the museum; let’s see, on the list the museum is No. 8 and the aquarium is No. 11, so I need to find 11 on the map and compare the location to 8. But there was ample space on this simple map for in-place labeling. Another good-looking map with marginal utility. I see these handsome but difficult-to-use maps everywhere—office complexes, universities, downtowns – and often as part of an otherwise effective wayfinding program.

Why so many ineffective maps? Many graphic designers treat maps as works of art, not as communication tools—abstracting reality into oblivion. Streamlining the complex environment into overly simple graphic forms and colors. Removing all pictorial references. Relegating wording and labeling to legend lists. But while taking pleasure in the purity of geometric forms and hardedge style, designers often leave the map user behind. Focusing only on the form, designers seem to know little of how people actually use maps.

Why so many ineffective maps? Many graphic designers treat maps as works of art, not as communication tools—abstracting reality into oblivion. Streamlining the complex environment into overly simple graphic forms and colors. Removing all pictorial references. Relegating wording and labeling to legend lists. But while taking pleasure in the purity of geometric forms and hardedge style, designers often leave the map user behind. Focusing only on the form, designers seem to know little of how people actually use maps.

We map users don’t ask for much; all we want is to easily find our present actual location on the map and effortlessly relate the map to its counterpart, the real world around us. A map is miniature interpretation of the world it represents and needs a few elements that I can look for in the environment and quickly see at the same time: a signature building, a major street, a public fountain. Anything to help match the map to reality around me. Then I want to locate my destination on the map and form a mental wayfinding plan—looks like the library is just up the street and two blocks over to the right.

We want up on the map to be the same as our direction of vision when reading the map – yes head-up maps are the only way to go. Sorry architects, but north-up just doesn’t work when you’re facing south in a busy city. Reinforcing our head-up map understanding is our ever increasing use of digital maps in our cars—I can’t imagine an Uber driver trying to find my house with an always north-up screen.

And, we want minimal mental work to do and that means avoiding or minimizing the use of legends—whenever possible all destinations should be labeled directly on the map.

But you can still design a cool-looking map.